Welcome,

readers. I’m chatting

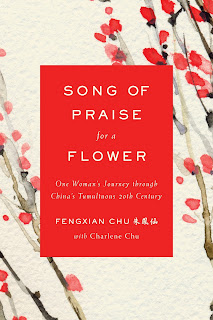

with Charlene Chu regarding Fengxian Chu’s memoir, Song of Praise

for a Flower.

(From

Charlene: Fengxian is now 92 years old. She isn’t up to doing interviews and

has asked me to handle everything, so the questions below are all written from

my perspective. I wrote the English version of the book – more on that below.)

Bios:

Charlene was

born and raised in Colorado and is half-Chinese. In her day job, she works as a

financial analyst covering the Chinese economy and financial sector, and in her

downtime, she writes. She is frequently quoted in the Wall Street Journal,

Financial Times, Bloomberg, Business Insider and other media outlets. Song of Praise for a Flower is her first

book. Charlene splits her time

between Washington, DC and Hong Kong and spends an inordinate amount of time

each year on planes and in airports.

Welcome, Charlene. Please tell us about

your current release.

Many years

ago, my now 92-year-old Chinese cousin, Fengxian Chu, wrote her life story for

her children and hid it in a bank vault. The manuscript sat there untouched for

two decades until I tracked her down several years ago filled with questions

about our family. Song of Praise for a

Flower is the English rendering of Fengxian’s memoir. It is a moving story

of resilience through adversity, the historical struggles facing Chinese women,

and China’s tumultuous transition into and back out of communism. It is a

living history of the past century in China, which arguably has seen more

dramatic change than anywhere else on the planet. Fengxian was born into a

world where it was common to bind women’s feet, forbid their education, and

hide them behind closed doors until marriage. With grit and fortitude, she

manages to break through these barriers, but later in life she is confronted

with devastating challenges during China’s transition into communism under Mao.

That she survived everything she did and at this late age is publishing her

story is a triumphant final chapter in a very difficult life.

What inspired you to write this book?

I saw

tremendous potential in Fengxian’s manuscript when I first read it. Most books about

the past century of Chinese history are either too academic, focused on one

concentrated period, or based on second-hand interviews. This is an engaging,

digestible, and rare first-hand account of China’s transformation over the last

100 years. The fact that this incredible story lay hidden in darkness in a bank

vault for nearly two decades and that I was the sole person in a position to

bring it to light was very motivating for me.

Excerpt from Song of Praise for a Flower:

Part One – Reminiscences of Huaguo

The Xiang River

For millennia, the

mighty Xiang (Syŏng)

River has pulsed

through the lush, rolling hills of Hunan Province in southern

China. The region’s

famous rice paddies derive their rich, green hue from the Xiang, and it is on the banks

of this river

that generations of Hunanese families

have flourished. In Chinese,

“Xiang (湘)” is the abbreviated name for Hunan, which I think makes perfect sense

because, whenever we natives think of home, often the first thing that comes to

mind is this beloved river. Several decades ago, when I was a young woman,

I bade farewell to the Xiang and have had the opportunity to

return only twice. Yet the river continues to run through my veins as vigorously

today as it did when I was just a little girl.

Nestled amid the long and winding

current of the Xiang River rests

the small, graceful village of my youth: Huaguo, or Flower and Fruit, in

eastern Hunan Province. Huaguo embraces miles of fertile land and luxuriant forest,

crisscrossed with green willows and tall bamboo.

Small homes dot the hillsides. Men cultivate the fields while women weave in

the courtyards, each working diligently every day. Grey-haired seniors play with lively children, bringing abundant smiles and

harmony to the village.

Huaguo is surrounded by numerous

hills to the north, east, and south and the Xiang River

to the west. Deep within

the hills are ancient

caves and dozens of narrow,

winding paths leading

to small valleys.

In this openness lie numerous small

brooks, gurgling and glistening in the

sun, and grass and wild flowers that emit a beautiful, delicate

fragrance. Huaguo is the kind of place the soul never forgets.

At the entrance of Huaguo stands

Fengmen Railway Station. Although not large, the station used to serve as a key

stop for trains passing through Hunan because of its proximity to the water.

Day and night, trains stopped at Fengmen Station to add water to the steam

engines, bringing business and swarms of passengers to the village.

The passenger cars, platform, and waiting hall would become

over-run with villagers hawking food and other goods, their cries

sonorous and rhythmic. Many of the hawkers

were young and as agile as monkeys, leaping across the tracks and climbing

into passenger cars. Sometimes these boys would remain on the train

selling goods even after it took off, jumping down fearlessly only after

the train reached full speed.

Not far from Fengmen Station was

a narrow street that used to form the center of town and was filled with small restaurants, stores, tea houses,

gambling parlors, and the local fortune teller. The street terminated at the

Xiang River, where several small ferry boats sat waiting to transport passengers across the water to the town of Fengmen, another village bustling with activity.

When I was growing

up as a young girl,

one of the liveliest times

of year was the annual Dragon Boat Festival, when teams from Huaguo and Fengmen would compete in a race on the Xiang River. The festival,

held on the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar calendar, commemorates the famous Chinese poet Qu Yuan,

who, according to legend, drowned himself in a river for his

motherland in 278 B.C. To distract the fish from eating the poet’s corpse, the

legend says that villagers threw rice and other food into the river. In honor

of Qu Yuan’s patriotism, Chinese people re-enact this event every year by

tossing pyramid-shaped dumplings into water.

The day of the festival, villagers from Huaguo and Fengmen would don their best clothes

and flock to the river

to toss dumplings and watch the race.

On both sides of the river, the streets and banks would be packed with a sea of horse carts and spectators. At the crack of a drum,

a dozen colorfully decorated dragon

boats would charge

ahead, splashing spectators with water as they sped down the river to the beat of the drum. The cheers of the villagers

would mingle with the roars of the drums and reverberate through the sky, awakening the God of Heaven

and Dragon King of the Ocean. After

the race, colorful

pennants would be handed to

each member of the triumphant team, and the audience would linger for hours,

basking in the joy of the moment.

The province of Hunan is said to

be a land flowing with milk and honey, with picturesque scenery and a soothing climate

of four distinct seasons. In spring,

plants sprout, flowers

blossom, and birds sing in joy. In summer, trees become lush and verdant. In autumn,

ripening fruits tug at tree limbs, and red and yellow leaves

fall to the ground signaling the approach of winter,

when leaves wither

and die, and a thin layer of white blankets the land.

Women of Hunan are known for their gentleness, courtesy, and passion. They love the young and respect

the old and are virtuous wives and mothers. Hunan’s

women are the shining pearl

of the province. It is no wonder so many ancient

emperors and leaders,

including Chairman Mao, came

from this magical environment.

What exciting story are you working on

next?

The first

line of my Foreword is “I moved to Beijing from the United States in 2006 for

the purpose of writing a book, but not this one.” I do have aspirations to

write another book, but I am so spent from this one that I intend to take a

very long break and enjoy the fruits of my labor.

When did you first consider yourself a

writer?

I’ve always known that there is a writer in me, yet I’ve never viewed myself as one until this book was published. Perhaps that’s because my main profession is in a completely different field. Fengxian, on the other hand, is a writer through and through. She has written poems and songs since a very young age. There is a scene in the book where Fengxian’s father tells her, “In life, it is inevitable that one encounters unexpected disputes and conflicts. You must struggle to the end, not with your fists, but nonviolently through writing.” That is precisely what she has done her entire life – as a youngster Fengxian used her writing to defy an arranged marriage; now as an elderly woman she has used her writing to not only to give voice to her own struggles, but also the challenges that hundreds of millions of Chinese people have endured over the past century. The vast majority of rural Chinese women of Fengxian’s generation never attended school and are illiterate, so it is extremely rare to have this kind of first-hand account from a Chinese woman of Fengxian’s age.

I’ve always known that there is a writer in me, yet I’ve never viewed myself as one until this book was published. Perhaps that’s because my main profession is in a completely different field. Fengxian, on the other hand, is a writer through and through. She has written poems and songs since a very young age. There is a scene in the book where Fengxian’s father tells her, “In life, it is inevitable that one encounters unexpected disputes and conflicts. You must struggle to the end, not with your fists, but nonviolently through writing.” That is precisely what she has done her entire life – as a youngster Fengxian used her writing to defy an arranged marriage; now as an elderly woman she has used her writing to not only to give voice to her own struggles, but also the challenges that hundreds of millions of Chinese people have endured over the past century. The vast majority of rural Chinese women of Fengxian’s generation never attended school and are illiterate, so it is extremely rare to have this kind of first-hand account from a Chinese woman of Fengxian’s age.

Do you write full-time? If so, what's

your work day like? If not, what do you do other than write and how do you find

time to write?

My job as a financial

analyst is incredibly demanding and consumes a large amount of mental energy.

Finding time to write Fengxian’s memoir was impossible Monday to Friday, so the

only time I could work on the book was during weekends and vacations. For several

years, I came home from work every Friday night, shut the door, and didn’t open

it until Monday morning when I went back to work. Occasionally during

vacations, I would do that for a week or more straight.

What would you say is your interesting

writing quirk?

My biggest

quirk is that I require total isolation to write. It’s the only way I can leave

this world and enter the world I am writing about. In the case of this book, I

had to switch gears from assessing mountains of data on China’s economy and

banks to writing about life in rural China in the mid-1900s. Not an easy task.

As a child, what did you want to be when

you grew up?

I loved building things. I thought I’d be something akin to an engineer. But as I became older, I became more drawn to social science rather than hard science and to writing. Although it was incredibly rare at the time for girls from rural China, as a youngster Fengxian had dreams of living in a city and becoming a modern working woman. She managed to break through many barriers during her era, but not this one. In the end, she became a rural housewife like every woman in our family that preceded her.

I loved building things. I thought I’d be something akin to an engineer. But as I became older, I became more drawn to social science rather than hard science and to writing. Although it was incredibly rare at the time for girls from rural China, as a youngster Fengxian had dreams of living in a city and becoming a modern working woman. She managed to break through many barriers during her era, but not this one. In the end, she became a rural housewife like every woman in our family that preceded her.

Anything additional you want to share

with the readers?

We’ve got an active Facebook page (click here) that features pictures related to the book, some info on the backstory, and posts linking the book to the present day in case people are interested. Fengxian and I both appreciate your taking an interest in the book. We hope it gives people a better understanding of today’s China and the historical challenges confronting Chinese women.

We’ve got an active Facebook page (click here) that features pictures related to the book, some info on the backstory, and posts linking the book to the present day in case people are interested. Fengxian and I both appreciate your taking an interest in the book. We hope it gives people a better understanding of today’s China and the historical challenges confronting Chinese women.

Thank you so much for being here today!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.